NAO report on HMT/HMRC management of tax expenditures

The National Audit Office (NAO) has published an interesting report on HM Treasury and HMRC management of tax expenditure, which includes some data on Gift Aid and VAT reliefs (principally VAT zero rating on construction of new dwellings – residential and charitable buildings).

The report highlights the lack of data in some areas, especially on VAT, which serves to highlight the importance of the CTG’s current VAT research project. The recommendations are a clear that there should be more scrutiny on the scope and impact of reliefs. HMRC apparently demonstrates no understanding about why the cost of the VAT RRP/RCP relief rose significantly over a four year period.

Key findings

The number and cost of tax expenditures

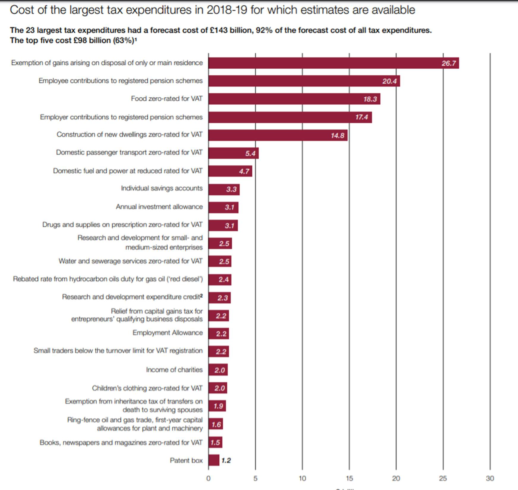

- Tax expenditures represent a large and growing cost to the Exchequer. In July 2019, the OBR reported that the known cost of tax expenditures had risen in the past decade. Our analysis of latest data published by HMRC in October 2019 shows that, between 2014-15 and 2018-19, the cost of tax expenditures increased by 5% in real terms, from £147 billion to £155 billion (forecast). Twenty-three tax expenditures each costing more than £1 billion accounted for 92% of the total forecast cost in 2018-19. The largest tax expenditures were the reliefs on pension contributions, the reliefs from VAT on food and new dwellings, and the relief from capital gains tax on people’s main homes.

- HMRC has committed to publishing more information on the cost of tax expenditures. HMRC has calculated the cost of 111 of 362 tax expenditures. It plans to estimate the costs for more tax expenditures between 2020 and 2022, prioritising those tax expenditures it regards as higher risk.

- The number of tax expenditures presents government with a significant oversight challenge. The International Monetary Fund states that tax expenditures require the same amount of government oversight as public spending. The scale of tax expenditures in the UK is larger than most other countries and it will be challenging to give tax expenditures the same amount of attention as spending. HMRC is improving its understanding of the different types of tax expenditures by categorising tax expenditures by purpose. Its initial work indicates that many are intended to incentivise behaviour. While HMRC’s new categorisation is useful in understanding the broad types of tax expenditures, it is not sufficiently detailed to group those targeted at similar sectors or those with similar social or economic objectives

The design and monitoring of tax expenditures

- The exchequer departments are improving their oversight of tax expenditures. In 2016 HMRC set up a central team to oversee its management of tax reliefs. The team identified the officials responsible for specific reliefs and established compulsory guidance. It introduced a framework to record information on reliefs in a consistent manner across the Department. In 2017, HM Treasury piloted monitoring of tax expenditures, prioritising those with specific policy objectives worth more than £40 million a year. By 2019 it had informally assessed whether 63 tax reliefs were value for money, as part of its policy-making process. The exchequer departments’ monitoring processes are still in development, and not yet integrated with one another. They plan to develop a single framework for administering and reviewing tax expenditures, drawing on relevant UK and international good practice.

- When designing tax expenditures, HM Treasury has not given enough consideration to how it will measure impact. When designing a new tax expenditure HM Treasury undertakes many of the activities that the NAO would expect at this stage including consulting with relevant stakeholders. However, the NAO did not find any cases among tax expenditures introduced since 2013 where government had set out plans for their evaluation at design stage, or triggers for evaluation if costs or benefits differed significantly from their forecasts.

- Some tax expenditures cost far more than government’s published forecasts indicated. HMRC does not compare the actual costs of tax expenditures to the government’s original published forecasts available to Parliament. HMRC told us that published forecasts are made on a different basis to the actual costs and a number of factors make meaningful comparison difficult. For example, the forecasts can include the impact on public finances of other changes to the tax system, other elements of tax revenue or wider economic impacts, which may not be directly comparable to the full cost of the tax expenditure. Even so, HMRC could take these factors into account to make meaningful comparisons, which would help it better understand costs. The NAO compared forecast and actual costs for 10 tax expenditures, adjusting for differences as far as possible with the data available. The comparison indicated large differences for some tax expenditures:

-

- For five tax expenditures introduced since 2013, including three of the four largest, data indicated costs were generally in line with original forecasts.

- For the R&D expenditure credit, and four smaller tax expenditures introduced since 2013, data indicated costs exceeded forecasts by 50% or more.

It was more difficult to compare forecasts and actual costs for tax expenditures introduced before 2013. However, the NAO found that the costs of three of our case study tax expenditures had grown from around £1 billion in 2008-09 to around £5 billion in 2017-18, much faster than the trends indicated in published forecasts (paragraphs 2.16 to 2.20 and Figures 10 to 12).

- HMRC has not fully investigated some large changes in costs. Cost increases may indicate that a tax expenditure is working well, or that it is being used in ways not intended. However, this can be difficult to determine without a substantive assessment. HMRC had identified reasons for large changes in cost for all the established case study tax expenditures the NAO looked at. However, it did not normally test how far the reasons explained cost movements, or compare its costs estimates with other data. Of the nine cases the NAO looked at, HMRC checked cost changes against independent data for only agricultural property relief and R&D reliefs. For R&D reliefs, HMRC compared the total R&D companies had claimed in tax returns for UK and overseas activity, with national statistics on total UK (only) R&D activity. This comparison revealed that the R&D activity companies had claimed was rising more quickly, and in 2016-17 exceeded all UK R&D activity by 43%. HMRC is in the process of investigating the reasons for trends in data

- R&D tax reliefs have been subject to increased levels of abuse. HMRC does not hold data on tax lost from abuse and error for all tax expenditures. However, it has developed a single view of the 63 main compliance risks it faces. Six of these risks are specific to tax reliefs. Some of the other risks partly arise from tax reliefs, although HMRC’s data do not show the significance of reliefs. Of the six tax relief-specific risks it has identified, the risks were increasing for three. The risk arising from the R&D tax expenditures was increasing the most. In 2017 and 2018 HMRC identified more tax at risk from poor-quality R&D claims, and from abuse by companies with a limited UK presence. In 2018 HMRC substantially increased its estimate of tax at risk from the R&D tax expenditures to a level which indicated further action was required. The time needed to train new staff and develop new systems has affected the pace of HMRC’s response.

The evaluation and review of tax expenditures

- HMRC has formally evaluated only a minority of tax expenditures. HMRC commissions and undertakes evaluations of few tax expenditures. Since 2015, HMRC has published evaluations of 15 tax expenditures, representing just 7% (£11 billion) of the aggregate forecast cost of tax expenditures in 2018-19. HMRC has evaluated only five of 23 tax expenditures costing more than £1 billion, and less than half of the large tax expenditures experiencing the fastest cost growth.

- HMRC’s evaluations of tax expenditures suggest that their effectiveness varies widely. Evaluations published since 2015 by HMRC have assessed the impact of 13 of the 15 tax expenditures covered. These evaluations found that seven of these tax expenditures (costing £3.6 billion in 2018-19) were having a positive impact on behaviour, and one (costing £1.4 billion) had had a mixed impact. However, five tax expenditures costing £5.2 billion had only a limited impact. Notably, a 2017 evaluation found that only 8% of people claiming entrepreneurs’ relief in the previous five years said it had influenced their investment decision-making. The relief costs the Exchequer more than £2 billion a year.

- HM Treasury has developed internal, informal processes for assessing the value for money of tax expenditures. HM Treasury reviews the tax system annually, including tax expenditures, as part of the Budget. In addition to this HM Treasury started a monitoring exercise in 2017 as a tool for collecting information and officials’ views to help inform advice to ministers. HM Treasury’s monitoring assessments have rated the value for money of 63 tax reliefs. HM Treasury told us these are internal, informal assessments that do not represent the formal view of the Department and should not be published because they are part of policy advice to ministers. The NAO looked at monitoring templates for eight case studies and found that the assessments ask many of the questions the NAO would expect, but that the quality of information underpinning the assessments was variable. HM Treasury was better placed to assess tax expenditures when it had information available from recent HMRC evaluations. In the case of the R&D expenditure credit HM Treasury based its assessment on an evaluation of the previous scheme aimed at large companies. HM Treasury undertakes limited quality assurance of its value-for-money assessments.

- There is no formal documentation specifying explicitly the departments’ accountabilities for the value for money of tax expenditures. In 2014, HM Treasury set out its view on accountability for tax reliefs but it did not specifically consider accountability for value for money. In 2019, HMRC informed the Committee of Public Accounts that the broader question of the value for money of tax reliefs is the responsibility of HM Treasury, with HMRC providing relevant advice as part of the tax policy partnership in the normal way. Policy decisions on the value for money of tax expenditures are for Treasury ministers, who are ultimately accountable to Parliament for the tax system and policy. HM Treasury officials are accountable for providing ministers with high quality advice to make those decisions. HMRC officials also carry out administrative functions which influence the cost and impact of tax expenditures. For example, clear guidance, promoting take-up to target groups, action to tackle abuse and timely reporting can all help to improve value for money.

- Public reporting has improved but does not yet provide the information necessary to assess the value for money of tax expenditures. HM Treasury ministers are accountable to Parliament for the value for money of tax expenditures. As part of the legislative process the government publishes costings and ‘tax information and impact notes’ and ministers outline their aims to Parliament. However, government does not publish the information necessary for scrutiny of the value for money of existing tax expenditures. HMRC’s statistical bulletin is much improved but still contains very limited information on the benefits achieved by tax expenditures, only limited commentary on their cost trends, and although HMRC included estimates for the number of claimants for the first time in January 2019, there is no trend data on the number of claimants. The bulletin does not explain how costs and benefits differ from the original published forecasts. Other countries have more comprehensive evaluation and reporting despite most having comparatively lower levels of tax expenditures.

Conclusion

- At a forecast cost of £155 billion in 2018-19, tax expenditures represent an important means by which government pursues economic and social objectives. Evaluations show that their impact is not guaranteed, and many require careful monitoring. The NAO have previously raised concerns about how effectively government is managing tax expenditures. Both HMRC and HM Treasury have responded to our recommendations by increasing their oversight of tax expenditures and actively considering their value for money.

- While these steps are welcome, they are very much still in development. The large number of tax expenditures means it will take time to identify and embed good practices. Both departments need to make substantial progress and ensure sufficient coverage and rigour in the work they undertake on this matter.

- On their own these improvements will not be sufficient to address value-for-money concerns unless the departments formally establish their accountabilities for tax expenditures and enable greater transparency. Lessons can be learned from other countries that have established clear arrangements for evaluating and reporting on tax expenditures. The NAO look to HM Treasury and HMRC to follow suit by clarifying arrangements for value for money and improving the evaluation and public reporting of tax expenditures.

Recommendations

- As the custodians of the tax system HMRC and HM Treasury are responsible for assessing the cost and impact of tax expenditures and communicating this to decision-makers. The NAO recommends that:

HM Treasury should:

-

- establish a framework for designing and administering tax expenditures that is commensurate with the large number of UK tax expenditures. The framework should draw on ‘Green Book’ principles, international good practice and stakeholder views

- develop a robust methodology for assessing the value for money of different types of tax expenditures, ensuring that assessments are quality-assured

- consider specifying time-periods or triggers for evaluation and review when designing each tax expenditure

- each year review whether the objectives of tax expenditures still align with government objectives; and

- establish and document clear requirements for officials to report concerns about the value for money of tax expenditures to ministers, for example by specifying accountability arrangements.

HMRC should:

-

- further develop categorisation of tax expenditures according to, for example, their objectives, scale, age and risks, in order to inform the allocation of administrative resources in proportion to the cost and impact that tax expenditures are intended to achieve

- identify and use independent data sources, where available, to further test reasons for movements in the cost of high-priority tax expenditures

- develop a more systematic approach to the evaluation of tax expenditures to provide greater coverage. The NAO estimate that the external cost of commissioning evaluations of six tax expenditures a year would likely be between £1 million and £1.5 million. This estimate does not include the cost of HMRC’s own internal costs, which could be significant

- develop an approach so that it understands and can report the differences between actual and forecast cost for tax expenditures it regards as high-priority in its published analysis. In cases where it is not feasible to make a comparison for a high-priority tax expenditure, HMRC should explain why

- include trend data on the number of beneficiaries of tax expenditures in published analysis, where possible, and take account of this within commentaries.